The architecture of heat: designing developments for a low carbon Scotland

Andy Yuill, Director of Asset Management, provides a detailed exploration of the critical factors to consider when selecting low carbon heating solutions for new developments. His insights shed light on the practicalities, benefits, and challenges of heat networks and heat pumps, helping decision-makers to make informed choices that align with their sustainability goals.

This article, originally written as a Practice Note for the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, examines one of the UK’s most pressing climate challenges: decarbonising the way we heat our homes and businesses. In Scotland, heating is responsible for approximately 15% of total greenhouse gas emissions, making it a critical focus area in the transition to Net Zero. Addressing this issue is essential to reducing the environmental impact of the built environment and meeting national climate targets.

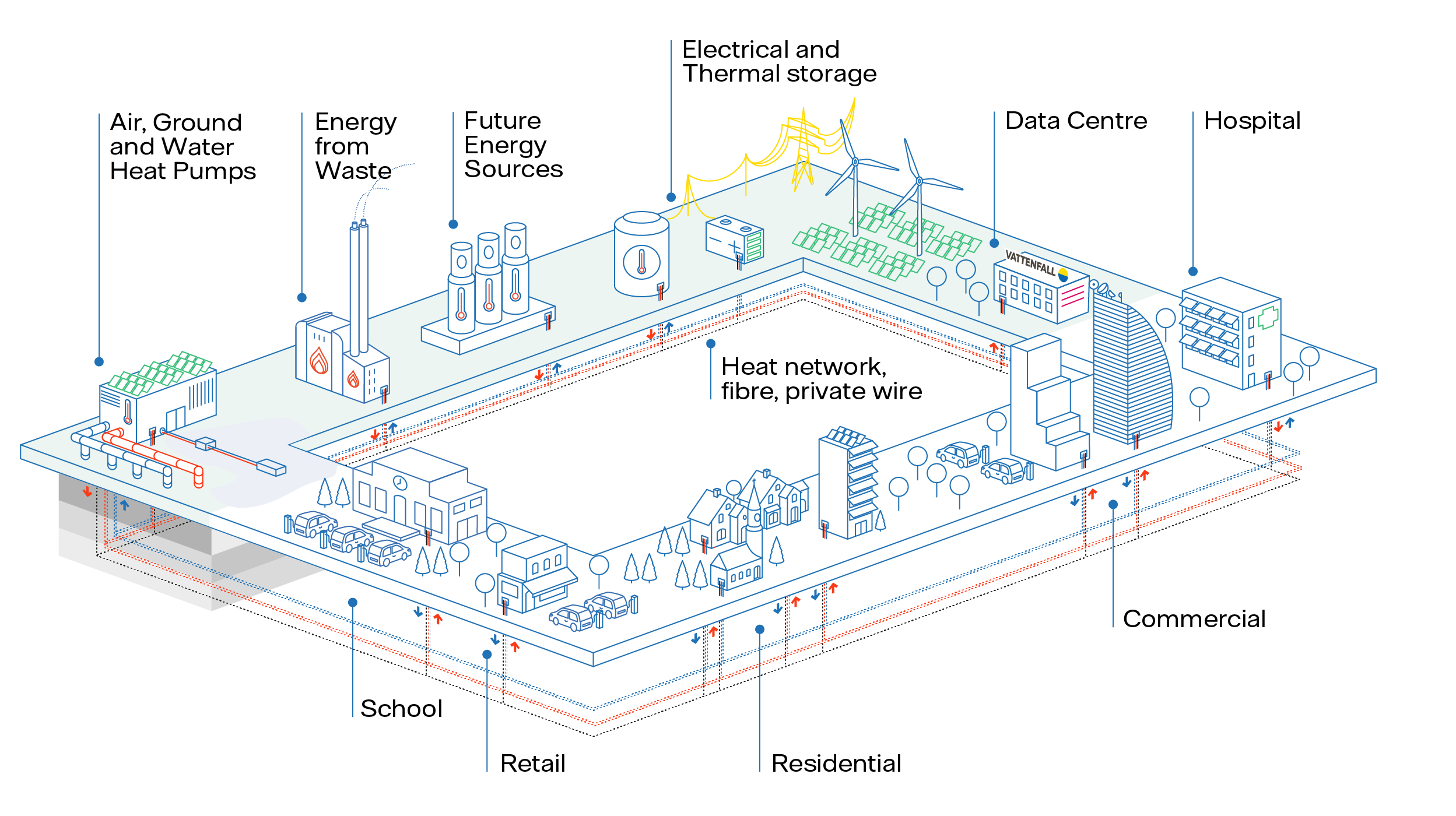

In recent years, the solution has become clearer: individual heat pumps for low-density areas and heat networks for higher-density towns and cities. At Vattenfall, we have over 100 years of experience in delivering low carbon heating, operating heat networks across Europe and providing daily heating and hot water to the equivalent of 600,000 homes.

The role of heat networks in Scotland

Scotland has set ambitious targets to increase heat network supply from under 2% in 2021 to 8% by 2030, contributing to its Net Zero goal by 2045. As the phase-out of fossil fuel heating systems accelerates, heat networks will become a key consideration in planning new developments.

Key considerations in choosing heat networks or heat pumps

When planning a new development, the decision to opt for a district heating system or individual heat pumps depends on several factors:

- Electrical infrastructure capacity

Heat networks use “demand diversity,” meaning not all dwellings will use their maximum heating capacity at once. This makes heat networks more efficient in terms of electrical capacity, unlike individual heat pumps, which can overwhelm infrastructure during a power cut. - Size of the development

Small developments (single-digit dwellings) are typically better suited to individual heat pumps. For medium or high-density projects, heat networks are often preferred due to lower electrical infrastructure demands and space efficiency. For large-scale developments (hundreds of dwellings), heat networks are generally the best solution. - Existing heat network infrastructure

If there is an existing or planned heat network nearby, connecting to it can be far more efficient than using individual heat pumps. Local authorities publish strategies for future heat network zones, providing insights for developers planning future connections. - Opportunity to use waste heat

Heat networks offer significant efficiency advantages, especially when using waste heat sources like energy-from-waste (EfW) plants or data centres. For instance, Vattenfall’s MEL Energy Centre in Midlothian will supply low-carbon heat to over 3,500 homes by utilising waste heat from an EfW plant. - Architectural benefits

Heat networks can free up valuable space in new developments. For example, by locating the heat network plant room on the ground floor, space in upper floors can be used for more desirable units with better views. This also benefits commercial properties by allowing more useable roof space.

Design considerations for heat networks

When opting for a heat network, several design factors must be addressed:

- Local energy centre: If no existing network is available, a small energy centre may be needed. This centre should be designed to connect to wider networks in the future. Heat Distribution: Heat distribution pipes must be carefully designed to minimise heat loss, with distribution systems optimised to suit the development’s density.

- Dwelling connection: The location of the heat interface unit within each dwelling is important. In single dwellings, it should be positioned near the entrance, while in flats, it can be located in communal spaces.

- Infrastructure: Heat interface units require minimal space, similar to a gas boiler, and do not need external units, making them more discreet and efficient compared to air source heat pumps.

The transition from fossil fuel-based heating to low carbon alternatives is essential for reaching Scotland's Net Zero goals. Heat networks, particularly in higher-density developments, are a crucial part of this shift. By carefully considering factors such as development size, existing infrastructure, and the potential for waste heat, developers can make informed decisions to support long-term sustainability.

Learn more about our current heat network projects in Scotland here.